Remember at school when you were shown how the various knobs and features of a guitar amp work? Me neither. You don’t want to be figuring this out on the fly when you turn up to your first jam, or when you’re trying out an amp in front of a pushy salesman. With that in mind, let’s have a bit of a tour around your average amp.

The Big Picture

Your guitar sound enters the amp at the input, gets shaped in the pre amp, and travels through any effects you may have in the effects loop. The power amp then takes that sound, makes it bigger and sends it to the speaker.

Sounds simple enough, but let’s take a look at how you can tweak that sound in each section of the amp.

Power on & Standby

It’s probably good practice to roll your volume down before turning your amp off, and make sure it’s still down before you turn it back on. I’m no amp tech, but the pop you get when you throw the power switch with the volume still up does not sound healthy for the amp. If nothing else, it’s a courtesy for everyone else in the room. Let’s face it, on a decent sized valve amp, that “pop” is more of a heart stopping “boom”.

As for standby, it’s largely debated as to whether there’s any point in using this feature. Most folks who know a thing or two about amps will tell you that this switch continues to be installed on amps as little more than a superstitious tradition. Having said that, if your manual tells you to leave your amp on stand by for a bit before using it, I don’t want to be the one to void your warranty.

Pre Amp

Inputs

If your amp has multiple inputs, you might be wondering which one you should be using, and why you need choices when it comes to simply plugging in.

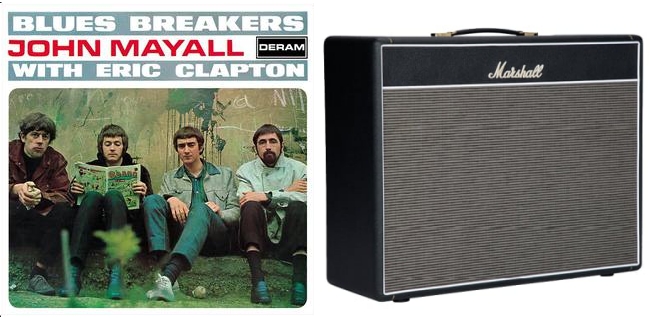

On Fender amps with two inputs, one of these will be for pickups with a low output and the other for higher output pickups like humbuckers. When you see four inputs on a Marshall amp, these will be a high and low sensitivity input for each of its two channels.

Bright Switch

Some guitars’ pickups are darker sounding than others. To accommodate for this, some amps will have a bright switch near the input socket which will kick in a little more treble.

Gain

The gain knob controls the signal strength coming into the amp. While originally it may have been intended as another consideration to adjust for pickups with different output levels, the far more popular use of this knob is to turn it up until the signal clips with overdrive.

EQ

The eq section lets you adjust the tonal characteristics of your sound by tweaking certain frequencies or certain ranges of frequencies.

If you want to sound impressive playing on your own, use lots of bottom end while dropping your mid-range for clarity. If you want to be heard at all in a band setting, you’ll want to do the exact opposite. Check out this article about working with overdrive to learn more about setting eq and gain for audibility in a band setting.

Tweaking your low, middle, and high frequencies is a straight forward affair while you have three knobs which correspond with them. What happens when you only have low and high knobs?

It’s simple enough once you get used to an eq like this, but it can be a real hurdle for newcomers. Both of these knobs affect themselves and the mid-range at the same time. Here are a few examples of how they do this:

- Low and high at halfway: mids are also at half way

- Low and high cranked: mids are scooped (turned down)

- Low and high turned down: mids are turned up

Multi-Channel Amps

On amps with more than one channel it’s not uncommon to find a row of gain and EQ knobs for each channel. It’s often the case that each separate channel is a separate pre amp circuit; although in some amps the second channel is actually just a higher gain setting with maybe a bit more treble. If that’s the case you probably won’t have much to tweak the second channel with.

There’s usually a footswitch you can connect to select which channel you want, but you might also find a switch on the amp that does the same thing.

Effects Loop

If your amp has an effects loop it’ll typically be on the back panel. To learn more about why you might want to use an effects loop, check out this article on pedal signal chain. Using the loop isn’t all that complicated. You plug a lead in from the “send” on your amp into the input of your pedal. The lead from the output of your pedal goes into the “return” of the loop on your amp.

Power amp

Master Volume

This one is pretty straight forward: it dictates how loud the power amp makes the signal before handing it to the speaker. I should clarify what’s happening here though.

Your power amp is actually always fully cranked, amplifying anything it’s given as much as it can. Much like how the gain knob controls how much signal comes into the pre amp, the master volume knob controls how much signal gets passed from the pre amp onto the power amp.

Presence

When you turn down the Master Volume, you might lose some of the high end from your tone. The Presence control is like a treble control for your power amp, allowing you to recover any lost top end once you turn the volume down.

Speaker Out

This is where you plug a lead from your amp to your speaker. It’s critical you don’t get this bit wrong. First of all, despite looking pretty much the same, instrument cables and speaker cables are different. Even though they both fit into these sockets, it’s important you only use speaker cables for this job, as using an instrument cable here could do damage. Plugging a speaker cable into your guitar would make it vulnerable to interference and noise.

The other thing to look out for here is making sure the amp impedance and speaker impedance match. I could (and probably should) write a whole post about speaker impedances and how to calculate the ohms for different combinations of speakers. For now though, just know that this requires caution. Don’t feel silly consulting your amp’s manual or asking for help from someone who knows about it.

One more caution about this part of the amp: if your amp is a valve amp, never turn it on without a speaker connected.

Dialling it all in

Quiet practice at home

Get the volume to a level you can work with, and then adjust the gain and eq to compensate for the overall reduction in sound. This is where the presence knob will come in handy.

With the volume knob on your guitar set to about half way, turn the gain on your amp up until it starts to break up, and then back it off a tiny bit. This will give you as much sustain and harmonic content as you can get while still having a clean tone. From there you can either use pedals for your drive sounds, use another channel in your amp, or simply roll your guitar’s volume up and hit the strings harder to push the amp into overdrive.

In a band setting

While the band is making a lot of noise, set your volume so you can hear yourself clearly. You won’t win a prize for being the loudest person in the room, and it’s pointless not having it loud enough for you and the rest of the band to hear.

Now adjust your gain as outlined above and set your eq to taste. It’s important to do all this while the band is playing at performance volume, as your audible frequencies are different in a band mix.

If you have the luxury of being able to play fairly loud, try this: Once you’ve got your clean sound dialled in with the pre amp gain at edge-of-break-up, turn the master volume up until the power amp starts to overdrive, then back it off just a little. Now when you push the amp into overdrive you’ll have both the pre amp and power amp breaking up. This is what people refer to as natural amp overdrive. If you only use the pre amp on its own for drive sounds, you’re missing out.