Effective pedal order is a subject that used to be treated as a great mystery, as though the correct signal path for each guitarist can only be known by them exclusively, and even then only after some kind of mystical revelation.

That’s absolute rubbish of course. People have been experimenting with their signal chains for decades now, common results have been documented, and a rough idea of best practice has been arrived at. In this post we’ll go over what that “best practice” looks like, why it works the way it does, and help you decide if, when, and how to “break the rules” so to speak.

Let’s get into it.

Standard Practice

Pitch

First of all, anything that needs to track the pitch of your guitar should get the cleanest, most unadulterated signal that it can if you want it to have a sporting chance of doing its job properly. By this I’m referring to your tuner, pitch shifters like the Digitech Drop and Whammy, and perhaps even octave pedals.

Gain

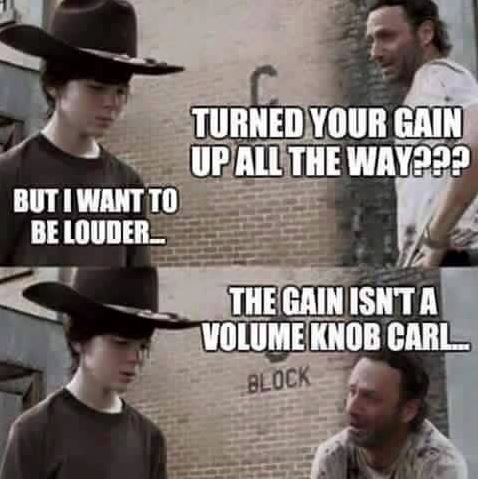

After that, it’s a good idea to have your drive section towards the start of the chain. This includes fuzz, overdrive, boost, and distortion.

Drive pedals typically define your EQ and gain level, which form the core, fundamental part of your tone. From that perspective it makes sense to establish this first before letting other pedals do freaky things with your core tone later in the chain.

Putting drive pedals after other pedals can radically change the way they sound. There are definitely situations where that can sound cool, but we’ll cover those later. For now let’s keep things fairly simple and vanilla.

Modulation

Next in the chain would be modulation pedals. This is the wobbly stuff:

- Vibrato (modulates your pitch up and down rhythmically)

- Chorus (splits your signal in two and applies vibrato to one of them)

- Phaser (splits your signal in two and moves them in and out of phase with each other)

- Flanger (splits your signal in two and adds a subtle delay to one of them, creating a swooshing effect)

- Tremolo (modulates your volume up and down, creating a shimmery or choppy sound).

Modulation pedals add character and create a sense of movement to the core tone you established in your drive section.

Time

After modulation we deal with time and space via delay and reverb. The idea of these is to take your whole signal and make it sound like it’s echoing back from or reverberating off the walls of a large space. For that reason you might want to send all of your effects into these.

The Fight for Last Place

Given that tremolo works by rhythmically dropping your volume, it’s possible that reverb tails or delay repeats which fall in that otherwise silent space might counteract the feel of it. For this reason, some people like to put tremolo at the end of their chain.

Then again, putting tremolo after delay creates the possibility of that silence coinciding with delay repeats, making it feel as though the delay isn’t turned on at all. The other possibility is your dry signal being silenced by the tremolo and only allowing the repeats through. The most likely scenario would be a mess of both. Best to experiment if you want to use delay and tremolo at the same time.

The Fight for First Place

For all their tough-guy image, some fuzz pedals can be total princesses about their input impedance. This means if they’re not the very first pedal in your chain they can behave like a spoilt brat.

Wah pedals typically go before your drive section to function properly, so if you have temperamental fuzz, you might have some experimenting and prioritising ahead of you. You’re in for a real headache if you have a fussy fuzz, a wah pedal, and a pitch-based effect that you intend on using at the same time.

The big picture looks something like this:

Pitch – Gain – Modulation – Time

I’ve seen some people on guitar forums post the chart below from Roland, stating that it’s all you need to know on the subject of signal chain. As we’ve just seen though, it’s not that simple.

There are a few issues that make it not terribly helpful for new guitarists trying to get their heads around signal chain issues:

- It makes no attempt to include a fuzz

- It does not tackle the tremolo dilemma

- It includes a Metal Zone. Honestly, what kind of message are they trying to send to new guitarists? What’s next? Handing out crack at a kindergarten?

Gain Stacking

Hopefully you’ve now got a decent idea of standard practice for the order of most pedal types. Within your drive section though, you might have a bunch of different types of gain pedals. Let’s have a look at how you might want to order them.

Just in case your fuzz pedal is the sort of entitled infant that will throw a hissy fit if it’s not first in line, we’re going to give it what it wants: Fuzz first.

Of course you love your Fuzz. It’s ok to feel sick of its bullshit from time to time.

From there though, you need to consider what you want your drive pedals to do.

If you want one pedal to provide a volume lift for another, you would place the heavier gain pedal first and the lighter gain pedal second. Order your drives from heaviest to lightest to get a big, high headroom drive sound.

If you want one pedal to add more distortion to another, you would place the lighter gain pedal before the heavier one. Order your drives from lightest to heaviest to end up with a chain of cascading nastiness.

Breaking the Rules

The number one piece of advice handed out to people who ask about pedal order is to “try it out for yourself”. Fortunately for you I’m not a complete asshole, and I acknowledge what a pain it can be to completely re-route your pedal board just to see what will happen. In this next part I’m going to try to explain the most likely outcome should you stray from standard practice.

That’s not to say you shouldn’t experiment. No one’s going to call the cops if you put your reverb first in your chain and your fuzz pedal last. There’s a pretty good chance you won’t enjoy the outcome, but you are of course free to do what you want. Experimenting and listening will no doubt give you a much better perspective than reading about it in a blog post.

Gain after Modulation

Placing drive after another kind of pedal will take its signal and compress it, smoothing it out and making it more consistent. With modulation, that kind of defeats the purpose.

Then again, maybe you have a modulation pedal that’s a little bit drastic for your tastes. Putting a subtle overdrive after it could tame it nicely. This would be a sensible reason to put drive after modulation.

Having said that, putting a killer high-gain metal distortion after modulation probably won’t be as kick-ass as you’re hoping. The distortion would sound more impressive with a clean signal going into it, and would only work to minimise and muddy-up the modulation.

Gain after Delay

Delay repeats typically decay or get quieter as they go on. If you put a drive pedal after it though, the compression will interfere with that decay. Repeats will continue for longer and potentially crash into each other. It’s a big, chaotic noise that might be fun to play with, but not what most folks have in mind when they reach for a delay pedal.

A slap back delay (one repeat with an extremely short delay time) can work either side of a drive without issue.

Gain after Reverb

Similar to the issue with repeat decay in delay pedals, putting a drive pedal after reverb will make the reverb tails carry on longer and create a big, chaotic noise. Again, fun to play with, but practically unusable unless you’re in a shoe-gazer band or avant garde noise act.

Using the Effects Loop

If your amp is already breaking up without the use of drive pedals, then your amp is acting like an overdrive pedal at the end of your chain. If you’ve taken anything from this article so far you’ll know this could be problematic.

While there’s probably a whole article I could write about how amps work, for now let’s just look at the two main parts: the pre amp and the power amp.

The pre amp sets the gain and EQ of your signal before handing it over to the power amp, which makes the whole thing louder. It’s the pre amp which is likely causing your amp to overdrive.

An effects loop lets you plug a few pedals between your pre amp and power amp. If you use your pre amp for your drive sounds, you can still maintain your signal chain by putting your modulation, delay, and reverb pedals in the loop.

What about a Phrase Looper?

There’s often confusion about where to put a loop pedal. These typically go at the end of your chain before your amp so they can catch everything, but again, you don’t have to do what everyone else does. Just remember that it will record anything you put in front of it, and its playback will be affected by anything you put after it.

Where Do I Put My EQ Pedal?

Put your EQ pedal wherever you feel the EQ correction needs to be made. If you’re trying to counteract a tonal quality of a specific pedal (like put some mids back in if you’re using a Muff, or bottom end if you’re using a Tube Screamer) put the EQ immediately after the pedal in question.

EQs can be fun to play with in your drive section. Just turning the level up can make it work like a boost. Cranking a specific frequency before sending your signal into a drive pedal will make that frequency overdrive more.

That’s All For Now

Hopefully that should cover most of the common questions that pop up around all things signal chain.

If I could impart any advice on the subject it would be to have a clear idea in mind about what you want to achieve before you start plugging things in, to save a lot of mucking around. Also, having said that, feel free to experiment and let your ears guide you.

Oh, and if you see this guy lurking around outside your school trying to sell Metal Zones: JUST SAY NO!